English 8600: Seminar in Writing Studies & Pedagogy

Spring 2020 | Syllabus

Instructor Information

William P. Banks, Professor

Director, University Writing Program

Office: Joyner 1009

Phone: 252.328.6674

Email: banksw [at] ecu [dot] edu

Office Hours: Tuesday & Thursday, 1:00 – 3:00 pm and by appointment

Introduction

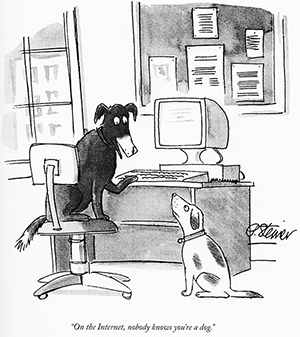

In Peter Steiner’s famous New Yorker cartoon from 1993, two dogs are talking in front of a computer, and one says to the other, “On the Internet, nobody you’re a dog.” This idea of the embodied freedom that would come from networked digital spaces pervaded many of the popular rhetorics around the World Wide Web at the end of the 20th century. Online, many hoped, we would be free of homophobia, racism, sexism, classism, etc — if people exit only as words on a screen, then how could readers possible know who these people really are? What will matter, folks thought, is only what’s written.

In Peter Steiner’s famous New Yorker cartoon from 1993, two dogs are talking in front of a computer, and one says to the other, “On the Internet, nobody you’re a dog.” This idea of the embodied freedom that would come from networked digital spaces pervaded many of the popular rhetorics around the World Wide Web at the end of the 20th century. Online, many hoped, we would be free of homophobia, racism, sexism, classism, etc — if people exit only as words on a screen, then how could readers possible know who these people really are? What will matter, folks thought, is only what’s written.

Of course, this absence of embodiment also meant, for some, anxieties: if you don’t know who you’re talking to, reading, engaging with, how do you know this person is “really” who they say they are? In the last twenty years, this issue has seemed especially pertinent, from the now famous example of “A Gay Girl in Damascus” to the work of ‘bots in the 2016 US election. Twenty-first century scholarship on digital cultures has often focused on how the promises of disembodiment were never met by networked digital spaces, while more recent work has looked specifically at how coding, algorithms, and other “invisible” parts of the Internet work to maintain racial, sexual, gender, and class-based inequalities, as well as promote acts of hate and violence. In this context, it is important to ask how digital rhetorics are also cultural rhetorics. This course looks at the rhetorical work happening in different digitally networked spaces in order to imagine the sort of literacy practices that participants in such space are developing — and to imagine how we might use college-level writing courses as sites of engagement and intervention.

Course Goals

Upon completing English 8600: Digital Cultural Rhetorics, graduate students should be able to

- articulate working definitions of digital rhetorics and digital cultural rhetorics that are both historically and personally relevant;

- recognize major shifts in how scholars have begun to conceptualize digital rhetorics as fundamentally bound up by cultural rhetorical practices;

- apply digital and cultural rhetorical theories to contemporary writing classroom contexts in order to understand how we might re-imagine writing instruction in multicultural and transnational digital contexts;

- locate, evaluate, and synthesize primary and secondary print and electronic bibliographic sources that contribute significantly to projects developed in consultation with the professor;

- propose and carry out a sophisticated seminar project which demonstrates 1) the ability to postulate an advanced thesis regarding digital cultural rhetorics, and 2) the ability to integrate course texts and individual research in ways that assist in supporting the thesis/argument of the project.

To meet these goals, graduate students will typically read between 150 – 200 pages per week, post responses to readings/activities on individual blogs, and engage in other projects listed below.

Required Texts

- Benjamin, Ruha. 2019. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge, UK; Medford, MA: Polity Press.

- Eyman, Douglas. 2015. Digital Rhetoric: Theory, Method, Practice. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. (Joyner)

- Gonzales, Laura. 2018. Sites of Translation: What Multilinguals can Teach Us about Digital Writing and Rhetoric. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. (Joyner)

- Keller, Daniel. 2014. Chasing Literacy: Reading and Writing in the Age of Acceleration. Logan: Utah State UP. (Joyner)

- Noble, Safiya Umoja. 2018. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: New York University Press.

- O’Neil, Cathy. 2017. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. First paperback ed. New York: Broadway Books.

Excerpts from the Following Texts

- Losh, Elizabeth, and Jacqueline Wernimont, Eds. Bodies of Information: Intersectional Feminism and Digital Humanities. Debates in the Digital Humanities Series. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Medina, Cruz, and Octavio Pimentel, Eds. 2018. Racial Shorthand: Coded Discrimination Contested in Social Media. Logan: Computers and Composition Digital P/Utah State UP.

- Pomerantz, Jeffrey. 2015. Metadata. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: The MIT Press. (Joyner)

Projects

The following brief annotations will provide some context for the sort of projects that this course will require this semester. More thorough explanations, where necessary, will become available over the course of the semester through the “Schedule” and “Assignments” links on this website:

- Reading Reflections — In order to foster both depth and breadth of thinking/coverage in the course, students will be responsible for creating weekly reading reflection that connect concepts, issues, and ideas from readings to the contexts of writing classrooms (e.g., first-year writing, scientific writing, business writing); students are encouraged to use different modalities and genres that synthesize key issues from readings and propose significant questions/problems for the class to address each week during discussion.

- Seminar Project Proposal/Drafts — Around midterm/Spring Break, students will propose an original study that connects digital and cultural rhetorics. Based on peer and professor feedback, students will design a research study and create a research proposal of roughly 8 – 12 pages (MA students) and 12 – 15 pages (PhD students) that reviews the relevant literature to demonstrate a key gap in current research and to propose a study for addressing that gap.

- Writing Course Redesign Project — During the second half of the semester, students will use their reading reflections to redesign/develop an undergraduate writing course (e.g., writing foundations, scientific writing, business writing, technical writing) to focus on and make use of digital and cultural rhetorics/literacies. For this project, students will create a syllabus, rough schedule, and set of major assignments.

- Presentation — As a peer-response activity, students will provide a 10 minute conference-style presentation of their writing course redesign toward the end of the semester, and will then have on week to revise the course design.

- Self Assessment — As a “final” or “summative” activity for the course, students will write self-assessments which demonstrate through examples from their work over the semester how they have met the course outcomes in order to receive they grade they have chosen for themselves.

- Studentship — Studentship refers to attending class, participating in face-to-face and online discussions, and meeting assigned deadlines for projects.

Grading Contract

This course makes use of a grading contract approach to evaluation. As such, individual projects do not receive grades; students are encouraged to do their best work in order to make the most of the learning experiences provided in the course.

Students who wish to earn an A should do the following work:

- Complete all projects/assignments by the posted due date, which means checking the course schedule each week for any updates or changes and planning accordingly;

- Produce Reading Reflections that clearly engage course readings and make connections to different contexts of writing instruction;

- Develop a compelling research proposal around course topics that both engages readings assigned in the course and demonstrates significant research beyond those assigned texts;

- Design an innovative version of an undergraduate writing course with all required materials that is shared with others in the class;

- Participate thoughtfully and fully in class each week and online by offering relevant, original insights, asking questions of peers, and connecting weekly discussions to previous readings/conversations;

- Communicate in a timely manner with the professor about any issues regarding missing class or work for either personal or professional obligations that may arise.

Students who wish to earn a B should do the following work:

- Complete the vast majority of projects/assignments by the posted due date, which means checking the course schedule each week for any updates or changes and planning accordingly;

- Produce Reading Reflections that clearly engage course readings and make connections to different contexts of writing instruction;

- Develop an appropriate research proposal around course topics that engages readings from the course as well as a number of studies beyond the texts assigned in the course;

- Design an undergraduate writing course with all required materials that is shared with others in the class;

- Participate in class each week and online by offering relevant insights, asking questions of peers, and connecting weekly discussions to previous readings/conversations;

- Communicate in a timely manner with the professor about any issues regarding missing class or work for either personal or professional obligations that may arise.

Students who wish to earn a C or less in the course should demonstrate less engagement than noted above.

Expectations

Obviously, I expect a great deal of commitment from graduate students. By choosing to tackle graduate school, you have plunged yourselves further into the world of the scholar. I hope you will enjoy that work and take advantage of this time to read, write, and think about issues and ideas you haven’t considered before, or to go further than you have in the past. “Reading” in graduate school, especially for doctoral students, is an exhausting activity. While I expect graduate students to “read” everything I assign, I hope that you will learn quickly how to “skim and save.” Do NOT try to read all these texts like you would poems or novels, pouring over each sentence looking for nuances of meaning. Try to get the big picture, isolate the key arguments/points in the text, and keep it archived for future reference. Develop coding and note-taking strategies for helping you to read the text now but will also prove useful in a year or two when you need that text again to remind you of key points and connections to other other texts. Some texts, I expect you to devour; others may not hold you interest. That’s normal. Regardless, I expect you always to have a passing acquaintance with ALL our readings and an engaged friendship with selected others. Obviously, I expect that we’ll have tremendous fun as we work hard together this semester.

Attendance

Graduate students by default should be at every class meeting, especially for a class which means only once each week. Emergencies and problems arise, so I can overlook your missing one week of class, especially since individual students can contribute significantly on the course blog the week they miss in order to “make up” for not being physically present. Missing more than once, however, will impact the course grade. Graduate classes rely on the presence of engaged students to be successful; as such, your absences will jeopardize learning for others, which isn’t acceptable.

Late Work

We all have very busy, trying lives, and as such, there come times when we have to complete some work late. Each student in this class is allowed an occasional late blog response, or other short piece of writing without falling below the “B” grade in the grading contract. Major assignments are set in stone and may not be late. Neither major projects nor drafts of major projects may be turned in late, as turning the drafts in late would invalidate the reason for drafting in the first place and turning in final projects late would prevent me from reading and evaluating them in time to turn in grades at the end of the semester. Students may always turn projects in early.

Conferences

Students should schedule conferences with me when they do not understand comments I’ve made on their projects or when they become confused about the expectations of this course. Likewise, I may require a certain number of individual and/or group conferences during the semester. After midterm, I will schedule conferences to discuss major project proposals.

Academic Integrity

Students are expected to be honest about individual effort and responsible to peer/secondary source materials that are included in their projects. Both plagiarizing and turning in work written partially or completely by someone else are forms of academic dishonesty and carry serious penalties, the least serious of which is a grade of zero on the particular assignment (and thus a D, at best, in the course), but could also result in failure of the class and even expulsion from the university. Students who keep up with their work and consult with their peers and their professor have no reason or need to “cheat.” Since this course is focused on research ethics, I expect that students will see me if they are unsure about how to cite or represent ideas/writing by others so that we can figure it out without ending up in a nasty plagiarism case.

Accommodations for Students (Updated 1/31/20)

Individuals requesting accommodation under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) should contact the ADA Coordinator at least 48 hours prior to the event at (252) 737-1018 / ada-coordinator@ecu.edu

ADA Accommodation: 252-737-1018 / ada-coordinator@ecu.edu